Michelangelo’s Pietà: A Comparative Study with Other Renaissance Masterpieces

Introduction

Michelangelo Buonarroti, one of the most renowned artists of the Italian Renaissance, created many masterpieces that have left an indelible mark on the history of art. Among his numerous works, The Pietà, sculpted between 1498 and 1499, stands out as a paragon of Renaissance art and religious expression. Located in St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City, this sculpture captures the poignant moment of the Virgin Mary cradling the lifeless body of Jesus Christ, embodying both technical brilliance and profound emotional depth.

The Pietà was commissioned by the French Cardinal Jean de Bilhères for his funeral monument. Michelangelo, who was only in his early twenties at the time, demonstrated extraordinary skill and sensitivity in rendering the marble into a lifelike representation of sorrow and grace. This masterpiece not only solidified his reputation as a leading artist of his time but also set a benchmark for sculptural excellence.

In this article, we will delve into a comparative analysis of The Pietà, examining its artistic context, its detailed elements, and how it stands alongside other significant works of the Renaissance period. Through this exploration, we will appreciate the unique qualities of The Pietà and its lasting influence on both Michelangelo’s career and the broader art world.

Artistic Context

The Italian Renaissance was a period marked by a renewed interest in classical antiquity and humanism, leading to significant advancements in art, literature, and science. Artists of this era sought to achieve a balance between naturalism and idealism, emphasizing proportion, perspective, and anatomical accuracy. Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and Raphael were among the foremost artists who embodied these principles in their works.

Michelangelo’s The Pietà was created during a time when artists were experimenting with new techniques and striving for greater realism and emotional expression. The Renaissance emphasis on humanism is evident in the lifelike portrayal of figures and the exploration of human emotions and experiences. This period also saw a shift from predominantly religious themes to a broader range of subjects, including mythology and everyday life, although religious art remained highly significant.

Other notable Renaissance works include Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper and Raphael’s School of Athens, each exemplifying different aspects of Renaissance art. Leonardo’s Last Supper captures a dramatic biblical scene with meticulous detail and innovative use of perspective. Raphael’s School of Athens, on the other hand, represents the intellectual spirit of the Renaissance, depicting great philosophers in a harmonious, balanced composition. By examining The Pietà within this artistic context, we can better understand its significance and how it reflects the broader trends of the Renaissance.

Detailed Analysis of The Pietà

Michelangelo’s The Pietà is a masterful composition that combines technical precision with deep emotional resonance. The sculpture depicts the Virgin Mary holding the body of Jesus after his crucifixion, a moment of intense sorrow and compassion. Mary is portrayed as a youthful, serene figure, her face reflecting a quiet strength and acceptance of her son’s fate. This choice to depict Mary as youthful and serene contrasts with the more traditional representations of her as an older, grieving mother, adding a unique interpretation to the theme.

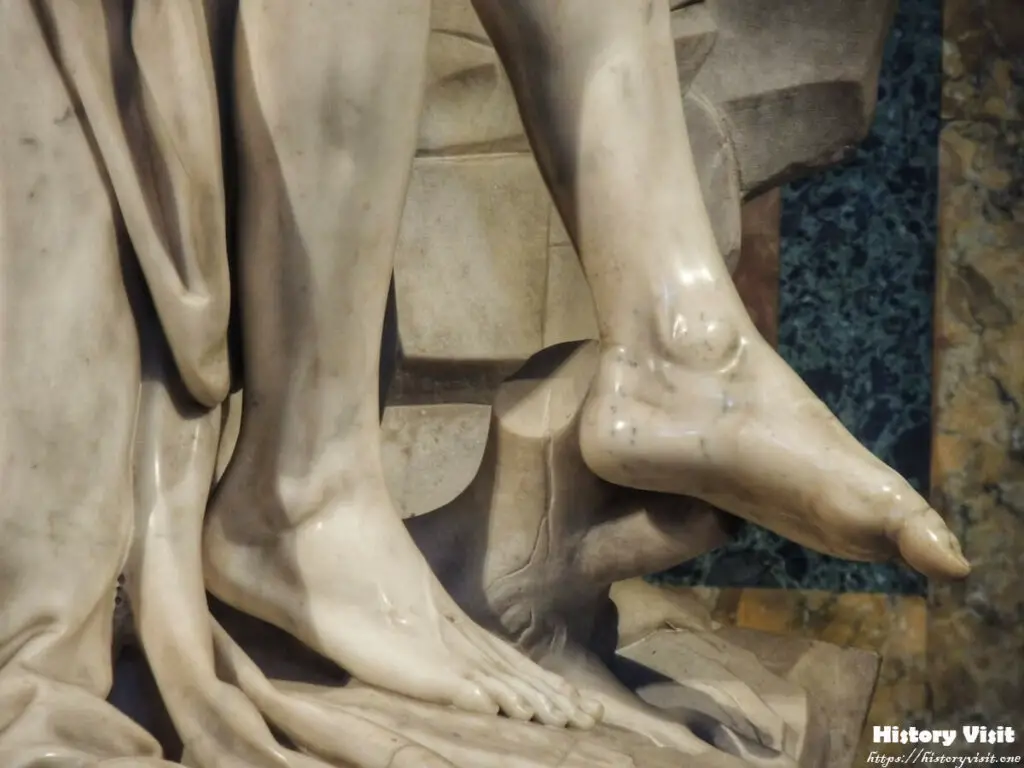

The composition of The Pietà is carefully balanced, with the figures arranged in a pyramidal structure that draws the viewer’s eye upwards, emphasizing the spiritual nature of the scene. Michelangelo’s skillful use of drapery enhances the naturalism of the sculpture, with the folds of Mary’s robe flowing elegantly around her, adding a sense of movement and life to the marble. The detailed rendering of Jesus’ body, from the anatomical accuracy to the depiction of his wounds, showcases Michelangelo’s mastery of the human form and his ability to convey both physical and emotional suffering.

One of the most striking aspects of The Pietà is the contrast between the smooth, polished surfaces and the intricate details. This contrast not only highlights Michelangelo’s technical prowess but also serves to enhance the sculpture’s emotional impact. The smooth, idealized faces of Mary and Jesus convey a sense of divine purity, while the detailed textures of the drapery and anatomical features add realism and depth, creating a powerful interplay between the divine and the human.

Comparison with Contemporary Works

When compared to contemporary works by Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael, Michelangelo’s The Pietà stands out for its unique approach to composition and emotional expression. Leonardo’s Last Supper, for instance, is celebrated for its use of perspective and the dynamic interaction between the figures. The scene captures the moment Jesus announces that one of his disciples will betray him, and Leonardo masterfully depicts the varied emotional reactions of the disciples, creating a sense of drama and tension.

Raphael’s School of Athens, another iconic work of the Renaissance, showcases a different aspect of the period’s artistic achievements. The fresco depicts an assembly of great philosophers and scientists, including Plato and Aristotle, in a grand architectural setting. Raphael’s use of perspective and harmonious composition creates a sense of order and intellectual grandeur, reflecting the Renaissance ideals of balance and reason.

In contrast, The Pietà focuses on a more intimate and personal moment, emphasizing emotional depth over dramatic action or intellectual themes. Michelangelo’s ability to capture the tender relationship between Mary and Jesus, and to convey a profound sense of sorrow and compassion, sets The Pietà apart from other works of the period. While Leonardo and Raphael excelled in creating complex scenes with multiple figures and intricate interactions, Michelangelo achieved a powerful impact through the simplicity and purity of his composition.

Influence and Legacy

The influence of Michelangelo’s The Pietà extends far beyond its initial reception. As one of his earliest major works, it established him as a master sculptor and set the stage for his subsequent achievements, including the statues of David and Moses, and the frescoes of the Sistine Chapel ceiling. The Pietà’s combination of technical skill and emotional resonance became a benchmark for later artists, inspiring generations of sculptors and painters.

The legacy of The Pietà is also evident in its impact on religious art. The sculpture’s depiction of Mary and Jesus influenced countless artists who sought to capture similar themes of sorrow and compassion. Michelangelo’s innovative approach to composition and his ability to convey complex emotions through marble set new standards for religious sculpture, and his influence can be seen in the works of later artists such as Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

Moreover, The Pietà has continued to resonate with audiences through the centuries, maintaining its status as a symbol of maternal love, sacrifice, and divine grace. Its location in St. Peter’s Basilica, one of the most significant religious sites in the world, ensures that it remains a focal point for pilgrims and art lovers alike. The ongoing admiration for The Pietà is a testament to its enduring power and the universal themes it embodies.

Critical Reception and Preservation

The Pietà has been met with critical acclaim since its completion, with contemporaries and later critics praising Michelangelo’s exceptional skill and artistic vision. Giorgio Vasari, a contemporary biographer of Renaissance artists, lauded The Pietà for its beauty and technical perfection, noting that it surpassed any work of its kind. This early recognition contributed to Michelangelo’s growing reputation and helped secure his place among the great artists of the Renaissance.

In modern times, The Pietà continues to be celebrated as one of Michelangelo’s masterpieces and a pinnacle of Renaissance sculpture. Art historians and critics have analyzed its composition, technique, and emotional impact, contributing to a deeper understanding of Michelangelo’s artistic achievements. The sculpture’s enduring popularity is reflected in the numerous reproductions and references in various forms of media, from literature to film.

Preservation efforts have been crucial in maintaining The Pietà’s condition, particularly after it was damaged in an attack in 1972. The sculpture was painstakingly restored, and protective measures have since been implemented to ensure its safety. These efforts underscore the importance of The Pietà as a cultural and artistic treasure, highlighting the need to preserve such works for future generations to appreciate.

Conclusion

Michelangelo’s The Pietà is a masterpiece that embodies the artistic and emotional depth of the Renaissance. Through its detailed composition and profound expression of sorrow and compassion, it stands as a testament to Michelangelo’s genius and his ability to transform marble into a living representation of human experience. The sculpture’s impact on both religious art and the broader art world is undeniable, influencing countless artists and continuing to captivate audiences with its beauty and emotional resonance.

By examining The Pietà within the context of Renaissance art and comparing it to the works of contemporaries like Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael, we gain a greater appreciation for Michelangelo’s unique contributions to the period. His ability to convey complex emotions through simple yet powerful compositions set him apart as a master of his craft, and The Pietà remains one of the most iconic representations of maternal love and divine grace.

The legacy of The Pietà endures not only in its artistic influence but also in its continued relevance to viewers around the world. As a symbol of compassion, sacrifice, and the human condition, it speaks to universal themes that resonate across cultures and generations. The Pietà’s enduring power and beauty ensure that it will remain a cherished masterpiece for centuries to come.