Gian Lorenzo Bernini: The Rape of Proserpina

A Baroque Masterwork of Movement and Emotion

Gian Lorenzo Bernini created The Rape of Proserpina at only 23 years old. It shows his genius early. This sculpture captures one of mythology’s most tragic and violent moments with shocking realism.

In the scene, Pluto abducts Proserpina, dragging her to the underworld. Gian Lorenzo Bernini carved the emotional terror and force in marble. The artwork feels alive, bursting with motion and emotion.

Few sculptures display such technical skill and raw energy. The Rape of Proserpina remains a masterpiece. Through it, Gian Lorenzo Bernini changed sculpture forever.

The Life of Gian Lorenzo Bernini: Rome’s Baroque Prodigy

Gian Lorenzo Bernini was born in Naples in 1598. His father was a sculptor too. Bernini grew up watching marble transform under skilled hands. His talent was clear from childhood.

The family moved to Rome. There, Bernini’s skill flourished. He studied ancient Roman art. He admired Michelangelo. But he soon found his own voice dramatic, emotional, and deeply alive.

By his twenties, Gian Lorenzo Bernini was already a star. Cardinals, popes, and noblemen commissioned his work. His name echoed in every Roman villa and palace.

His art was not just beautiful it moved people. Bernini’s goal was to make stone feel like flesh, breath, and thought. In The Rape of Proserpina, he achieved that vision fully.

The Myth Behind the Marble: Proserpina and Pluto

The story of Proserpina comes from Roman mythology. She is the daughter of Ceres, goddess of harvest. One day, Proserpina walks in a field. Pluto, god of the underworld, sees her.

He falls in love or lust and seizes her. He drags her down into his dark world. Ceres searches desperately. Crops wither. The earth mourns.

Eventually, a compromise is struck. Proserpina must spend part of the year with Pluto. The rest she returns to her mother. This myth explains the seasons. Winter reflects Ceres’ grief.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini carved the moment of abduction. He caught the horror, force, and sorrow in action. Every gesture, every detail adds to the narrative’s emotional power.

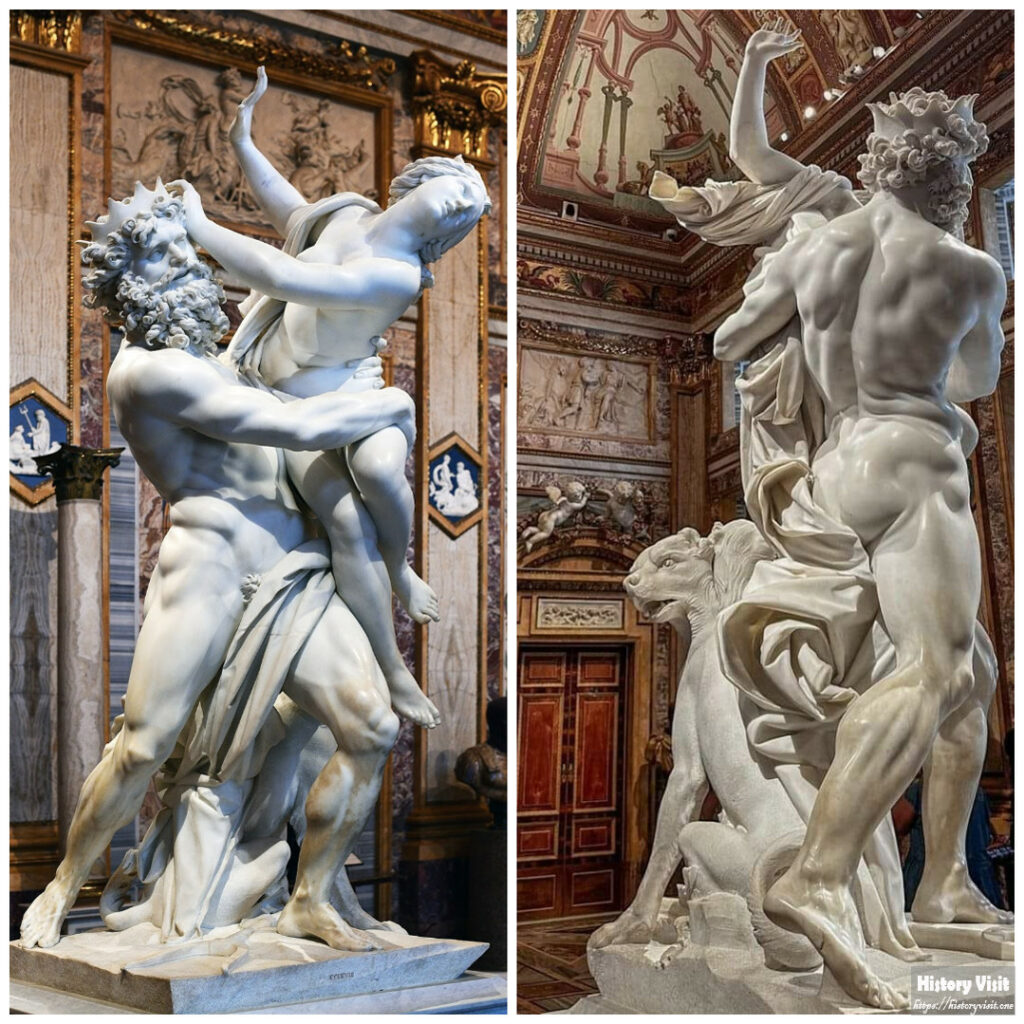

Composition and Technique: Marble That Breathes

Gian Lorenzo Bernini turned marble into life. In The Rape of Proserpina, every surface pulses with movement. Proserpina pushes against Pluto’s force. Her fingers dig into his face.

Pluto’s grip is firm and invasive. His muscles strain. His fingers press into her thigh. The skin dimples. The illusion is shocking. It looks soft, though it’s solid stone.

Proserpina’s hair flies back. Her mouth is open. She screams, silently. Pluto’s cloak swirls around them. A three-headed dog, Cerberus, snarls at their feet.

This sculpture was not just carved it was choreographed. Gian Lorenzo Bernini balanced chaos with control. Every fold and line guides the viewer’s eye in a spiral of drama.

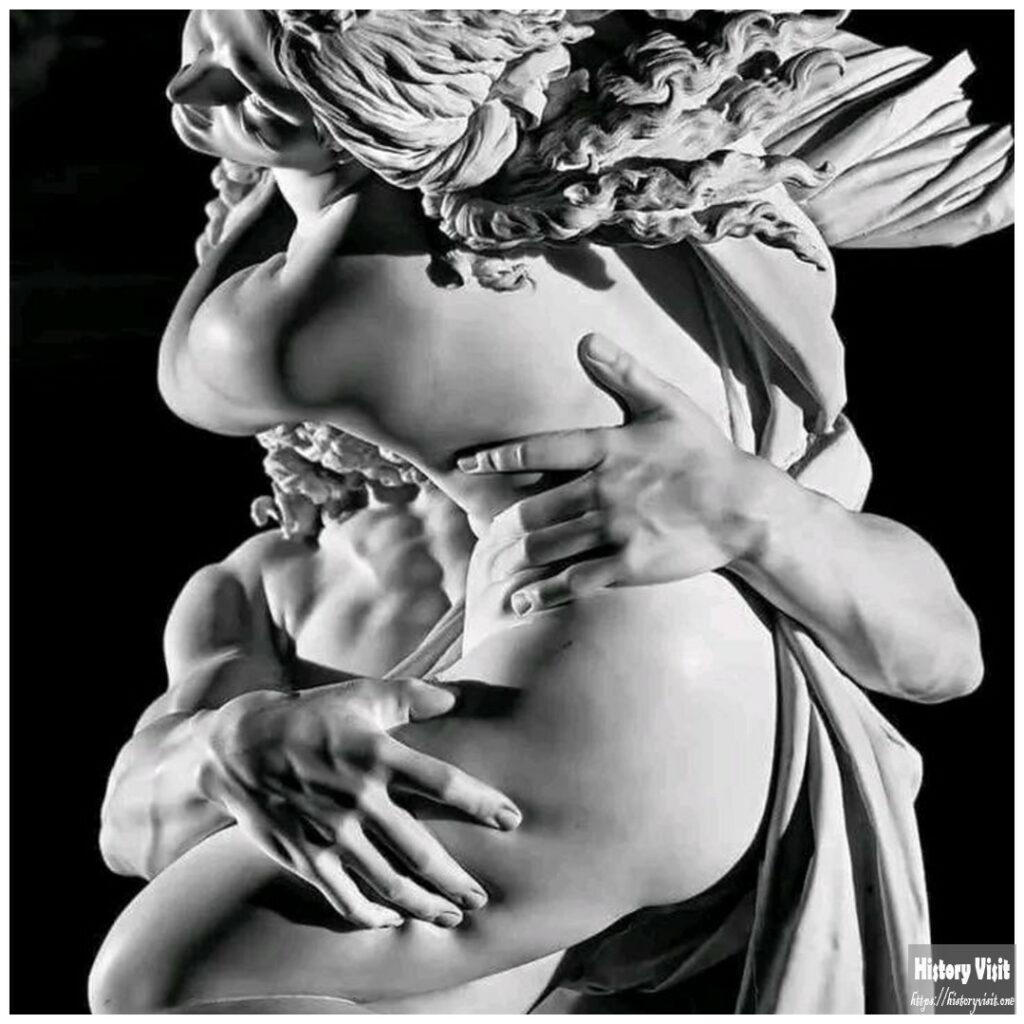

Realism and Emotion: The Signature of Gian Lorenzo Bernini

Realism defines Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s approach. He studied anatomy closely. He observed how skin moves, how muscles shift. That knowledge lives in every part of the sculpture.

Look at Proserpina’s tear. It’s carved. Still, it looks wet. Her hand resists Pluto’s shoulder. Her toes stretch in protest. The fear and struggle are carved, not imagined.

Pluto’s face shows hunger and cruelty. His mouth clenches. His eyes stay fixed on his prize. His whole body moves with predatory purpose.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini didn’t shy from pain. He made us feel it too. His art demands more than admiration. It forces emotional connection. In The Rape of Proserpina, feeling becomes visual.

Patronage and Politics: Why the Work Was Commissioned

Cardinal Scipione Borghese commissioned the sculpture. He loved dramatic mythological art. He wanted something bold. Something unforgettable. Gian Lorenzo Bernini delivered that and more.

Rome in the 1600s was about power and spectacle. Cardinals were princes in all but name. Art was a tool for status. Owning a Bernini was a mark of taste and might.

Borghese displayed the sculpture in his private villa. Visitors were stunned. The sculpture became a talking point across Rome. It was proof of Borghese’s wealth and Bernini’s genius.

The Church also supported Bernini. They saw his power to inspire. Though this sculpture was secular, it built his fame. Gian Lorenzo Bernini was soon sculpting saints and popes too.

Placement and Scale: Space as a Storyteller

The sculpture stands over seven feet tall. It’s almost life-size. That scale makes it immersive. Viewers don’t just see the story they enter it.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini designed it to be seen from all sides. Each angle reveals new emotions. Pluto’s grip, Proserpina’s scream, the dog’s snarl they circle the viewer.

The original placement was crucial. The statue was displayed in a light-filled room. Light danced on the polished surfaces. Shadows deepened the folds and creases.

Modern museums keep the same effect. Light and shadow play across the figures. The room becomes part of the sculpture. That’s how Gian Lorenzo Bernini wanted it art and space united.

Influence and Legacy: Changing the Future of Sculpture

Before Gian Lorenzo Bernini, sculpture was often still and composed. Figures stood calmly, posed like gods. Bernini broke that rule. He brought motion, emotion, and narrative.

Artists across Europe followed him. His influence spread to France, Spain, and beyond. The Baroque movement grew stronger. Sculptors tried to copy his realism and drama.

Later artists praised Bernini. Even centuries after his death, they studied his techniques. Rodin admired him. Michelangelo inspired Bernini, but Bernini became a beacon too.

The Rape of Proserpina remains in art textbooks, museums, and films. It’s still a benchmark. If marble can bleed, Bernini showed how. His power changed art forever.

Comparing with Other Bernini Works

Gian Lorenzo Bernini created many masterpieces. Apollo and Daphne is one. It also shows myth and motion. Daphne turns into a tree as Apollo reaches her.

Another is David, mid-swing with a sling. The tension in his body mirrors Proserpina’s resistance. Bernini loved action. He hated stillness. His statues breathe in every corner.

Compared to those, The Rape of Proserpina is rawer. It shows violence, not pursuit. It shows no escape. That gives it deeper emotional weight.

All these works show Bernini’s core style. Curved motion. Emotional faces. Realistic textures. Together, they define the genius of Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

Public Reaction Over Time

Early viewers were stunned. Many asked, “How can marble be this alive?” They admired the skill and boldness. Some were shocked by the violence, but all respected the craft.

Over centuries, reactions shifted. Some saw the work as too dramatic. Others praised its passion. Feminist critics questioned its message. Was it glorifying abduction? Or showing its horror?

Today, most see it as a mix of both. The artistry is undeniable. But the content invites discussion. That’s Bernini’s power—he made viewers feel and think.

Museums protect the statue carefully. Visitors line up to see it. Phones capture every detail. But the experience must be felt in person. Gian Lorenzo Bernini built art that lives on.

A Close Look: Hidden Details in the Sculpture

Look closely at Pluto’s hands. They aren’t just gripping. The fingers press deep into flesh. That detail took genius. Gian Lorenzo Bernini made it seem soft and bruised.

Proserpina’s hair flows in waves. It adds motion. Each strand was carved by hand. Nothing was rushed. Even the tears on her cheek hold expression.

The dog, Cerberus, adds meaning. It roots the scene in the underworld. Its heads snarl in different directions. It too resists Pluto’s command.

These small touches add depth. They build the story. They show Bernini’s attention. Nothing was left to chance. Every inch serves a purpose in The Rape of Proserpina.

Art That Lives and Binds

Gian Lorenzo Bernini captured myth, movement, and emotion in one breathtaking sculpture. The Rape of Proserpina is not just art. It’s an event frozen in stone.

The piece stirs awe and discomfort. It tells a story of power and helplessness. It shows love twisted by force. Bernini carved both beauty and brutality.

His legacy lives on in every artist he inspired. His sculpture still teaches. Still moves. Still shocks. Thanks to The Rape of Proserpina, Gian Lorenzo Bernini remains forever alive in marble.